I think this is a wonderfully evocative image. It's just as I imagined as a child, a magical place and to my young mind, no hint of the hardships that must have been suffered by the people who lived there.

The word Belvedere means 'beautiful view' in Italian and Upper Belvedere was a much sought after area for wealthy city commuters. In contrast, Lower Belvedere attracted a smaller, less wealthy population and this may have been due to its close proximity to the nearby marshland. Much of the marshland around the railway station was occupied by gypsies and I can remember mum telling me about them. What she saw was probably not much different from this photograph of the Belvedere gypsy camp in the 1930's, I think they look rather exotic!

Mum also used to tell my sisters and I about her hop picking holidays and I was fascinated by these stories. Hop picking was at it's height from the 1920s to the 1950s and it was traditional for poor Londoners, mostly women and children, to travel to the rural Kent hop gardens at the end of summer to pick hops, then the counties most important crop. It was commonly known as the 'Londoner's Holiday' as it was the closest many people got to taking a break. Though it must have been very hard work I imagine a change of scene and the social side of things, meeting up with old friends in the wide-open spaces of rural England, would have been something they all looked forward to.

Life changed with the onset of WW2. Living so close to London the family witnessed the war first hand. The River Thames was used as a guide by German bomber pilots and the Woolwich Arsenal was a prime target, so Belvedere came under heavy fire. Picardy Street was flattened, as were many other local areas. This excerpt from the recollections of Ivy Houseago from 'Belvedere Stories' describes what it was like.

"We had a lot of bombs around here, because we're near to the river and about four miles away is the Woolwich Arsenal, so it was a good target. Picardy Street was flattened. Then in 1941 we were bombed out here - where I still live. As it happened we'd had a lot of damage, we had no windows in the back of the house ..... Those Bombs did awful damage, they changed Belvedere for ever.”

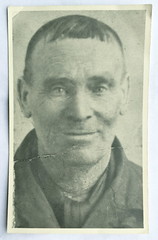

This is a photograph of Patrick Hayes. I never met my Grandfather and this is the only photograph I have ever seen of him.

To escape the danger, my grandfather brought his family up to the Staffordshire Potteries in 1941. They came because my grandmother Mabel had a sister, Florence, who lived in Heron Cross. I think they lived with her temporarily before moving to their own home, no. 4, Railway Terrace, East Vale, Longton.

A photograph of Railway Terrace dated 1930-39 taken from Paragon Road.

Source: Staffordshire Past Track

In many ways The Potteries were not unlike the area the family left, built up and heavily industrialised. Until the Clean Air Act was passed in 1956, Longton would have been a dark and smokey place. Smoke churned out of the bottle ovens day and night. From the 18th century until the 1960s the bottle ovens were a dominating feature of the Staffordshire Potteries. There were over 2000 of them standing at any one time and they would have been seen in every direction. Even nowadays the area is fondly referred to as 'Smoke on Stench'!

Half a century earlier, the author Arnold Bennett, in his novel Anna of the Five Towns referred to Longton as Longshaw. He compared it to being akin to Hell.

"Pictures of the area during its industrial growth defy belief with smoke pouring from a multitude of chimneys in amongst bottle ovens of various shapes and sizes. The great concentration of these ovens and the situation of Longton being in a slight hollow, made it the most polluted of all the pottery towns." Arnold Bennett | Arnold Bennett's Longton.

Before long, life for my mother began to get back to some kind of normality and on the 2nd September 1941, aged five, she was enrolled at St. Gregory's Catholic School. In the school's Admissions Book she was registered as an 'Official Evacuee'. The evacuation of civilians in Britain during the Second World War was designed to save civilians in Britain, particularly children, from the risks associated with aerial bombing of cities by moving them to areas thought to be less at risk. Operation Pied Piper, which began on 1 September 1939, officially relocated more than 3.5 million people. Further waves of official evacuation and re-evacuation occurred in June and September 1940

On the 29th July 1943 she left the Infants School and on the 23rd August that year joined the Juniors. Mum's schooldays were not particularly happy. She always said the nuns were very harsh and I know she struggled academically. This page from one of the school log books, filled in by the Head Teacher, records the day to day activities, many which would still be familiar in schools today, for example Christmas parties and day trips. Some of the trips and parties commemorated important national events including this visit to Trentham Gardens to celebrate the end of the war; it must have been very exciting for the children.

When mum wasn't at school one of her favourite things to do was to play in Queen's Park, or Longton Park as it was known locally.

This recollection by my Aunt Beth tells of the time she spent the day with mum who was told to look after her, so mum reluctantly took her along with her and some friends to play in Longton Park. It couldn't have been much fun having your little sister tag along, and in amongst it all mum forgot all about Beth and went home without her.

You might have thought that it was a frightening experience for a young child but Beth has very happy memories! She was found by a very friendly lady who lived nearby in one of the beautiful big Victorian houses that border the park. She was very well looked after, bathed and fed and spent the night there until being collected and taken home the next day. My Aunt loved being there, so very different from living in a small terraced house with a large family, 6 brothers and sisters all fighting for attention.

It was not such a happy ending for mum though, she was in a lot of trouble for forgetting her little sister, but I think easily done when you're having fun!

My mother left school in 1950 aged 15 years and as was the custom, she found a job straight away. There was no shortage of work in the numerous pottery factories and Mum stayed close to home and began a job at Aynsleys, on Sutherland Road, a few minutes walk from her home on Railway Terrace.

Aynsleys was established in 1775 by John Aynsley and was situated in Lane End, as Longton was then called. John Aynsley was originally a decorator but by 1810 records show that a maker of earthenware called Aynsley and Company existed in Flint Street, Lane End, and they were the first to specialise in lustre ware, an iridescent effect achieved by applying a metallic glaze. John's son James took over the business and after James, his son John 2nd who founded the Portland Road works in 1861. These buildings still stand today although the factory sadly stopped production in late 2014.

Historically, Longton was known as a producer of bone china and Aynsley's was the longest surviving original manufacturer. Their early ware was decorative china, hand painted and gilded and this specialism continued until production ceased. Aynsley's had always produced a top range of products that were luxuriously decorated and hand gilded in gold and platinum. Mum was involved in both of these distinctive processes, applying the patterns and later the gilding and I've been lucky enough to learn all about mum's time at Aynsley's from my Aunt Beth.

These memories of my Aunt's, who has lived in New York for over fifty year now, are very precious to me. They helped to paint a wonderfully vivid picture of the relatively short period of time my mum spent working at Aynsleys.

At the time Beth was still at St. Gregory’s and mum managed to get her a job after school doing the 'cake run'. She would come into mum's workshop about 3.30pm and take the cake order for the ladies who mum worked with, then run over to the tiny cake shop across the road with the order before returning with the cakes. This allowed her a glimpse into mum's world of work. Beth did this two or three times a week for a little over a year.

"On Fridays I would be paid, half a crown, that was a lot of money for me and your mum thought they were being too generous, but she didn't say anything!"

Here are some more of her memories: She remembers men and women working separately, men tending to do the heavier work. Also, all the top bosses and managers were men.

Beth said mum got the job through the sister of a friend and worked long hours. Monday to Friday mum left home at 7.30am and was seated at her bench and ready for work by 8.00am and finished at 5.00- 5.30pm. It was common to work Saturday mornings too. There was a fifteen minute break in the morning and afternoon and a longer break for lunch. Beth can't remember what mum earned but said she certainly would have given her mother at least half, maybe two third each week!

“There was no dress code but everyone wore an apron or a wrap around overall. The bosses and manages wore a white 'cover coat'. Mum's first job was training to be a lithographer and there were about 20 other women in her 'shop' or workroom. A lithograph is a design in ink that is applied to tissue paper. The paper is wet and the design is then laid onto the china, left to stand before carefully removing the paper leaving the inked design on the piece of china. It was quite skilled work. The room was laid out with long wooden tables facing a large window. Two ladies in a senior position worked on all the samples and new designs and they would work directly with the managers. Your mother Catherine sat with these two women and she was the youngest worker. Each worker had her own chair at the table, (I think there were four women per table).

One of her jobs entailed taking the finished samples to the 'big cheeses' whose offices were situated on the top floor of the factory that meant walking up many steps! She hated doing this because she was afraid she would slip and break the sample, plus she was shy and felt uncomfortable knocking on the office door and handing the samples over. One Saturday, when few people were around, she showed me a couple of the other workshops and the way to the offices and Jane, believe me, one had to be sure-footed to get to these places.

Another job your mum did for the two ladies, one was called Mary by your mother but Mrs. Mary by everyone else, was to change the pails of water that were used for the transfers. She had to go through two other 'shops' to get to the cold water tap. Twice a day she did this, and for her own pail but it didn't seem to bother her”.

“Your mum worked in the decorating end of the factory, not the clay end and I used to see some lovely pieces of fine bone china that landed on her sample table. Catherine would tell this or that order was going to America, I had no idea were America as then, it could have been on the moon for all I cared. Isn't it funny how things turned out?

I saw what I thought was the most lovely teapot that had fruit painted on it. About twenty years ago I found one in England of the same design made by Aynselys and bought it because it reminded of the days with your mum, and of course, I love it.”

“There is something I remember vividly, that may not be relevant, but is interesting so I'll tell you anyway. One afternoon, after bringing the cakes in your mum informed me that a young man would be coming in to speak to either Mary or the other lady. She said I was not to stare at him when he came or she would slap me hard. This meant of course, that I had to see him! As he approached the bench the first thing I noticed, as I was looking down, were his nice shoes. I continues to look up and saw his trouser legs, his beige top coat, not white, and finally his face.

That's when I was taken aback. He was wearing heavy cosmetic foundation, rouge, lipstick, eye shadow, no mascara that I can remember and his eyebrows were pencilled in. He spoke with a lisp and Mrs. Mary called him Eric. This was my first encounter, and I'm sure your mum's too, with an openly feminine male.

Your mum told me he was one of the top designers and I saw him often after that and he always gave me a nice smile. Once, I heard him telling a younger man to 'Have Cathy, the sample girl in the lithography shop to come by and pick up some sample'.

Your mum was well liked by everyone in the workshop, not just because she was the youngest but also because she was conscientious and hard working and very polite.”

“I have often wondered why I was allowed to do the cake run. I was only about ten years old and cannot remember ever seeing other children in the factory and even then there must have been Health and Safety rules. Perhaps people felt sympathy towards us. Consider the times, the bombing in London was only a few years earlier. Grandma, your Uncle Pat, Uncle Michael and your mum would have spoken with a southern accent and everyone would have known we were displaced evacuees and our clothes would have indicated we were poor. Maybe that was why they made allowances and tried to help the family out.”

“There were not the same holidays we have now but there was always 'Potters Fortnight', in June or July I think, when all the factory's closed down for two weeks in the summer. We always knew when it was Potters Fortnight by listening to the sound of footsteps coming down the alley in the early morning. To my young ears it sounded as if everyone was wearing clogs, but they were not. Your mum and I would peep through the bedroom window to see the singles, couples and families carrying suitcases, bags and paper wrappings (probably for sandwiches to be eaten on the train), and we would try to guess these holidaymaker's destinations. Of course it was mainly Blackpool and everyone always looked extraordinarily clean!”

I have also been very lucky to have been in contact with a contemporary of mums at Aynsleys. Her name is Joan Mooney and she got in touch after I wrote an article for The Sentinel, the local paper. Joan corroborated some of what Beth told me, particularly about the work breaks. She said most people had bacon and toast at break time and that another of mum's jobs was to go round the factory each morning and sell tickets that were redeemed in the canteen at lunch-time when sandwiches were the norm.

Joan also told me that mum didn't stay in the lithography shop for long and that she moved to 'gold scouring'. This is how she explained it.

“Once the gold had been applied to the china, it was fired and came out of the kiln dull. The job of the gold scourers was to polish it. This was done by using a special cloth, new every month, dipped in water, then some sort of sand to gently polish up the gold. Joan said that a supervisor called Lily Perry took a liking to Mum and took her under her wing. Lily used to take home laundry for the managers to earn a bit extra!

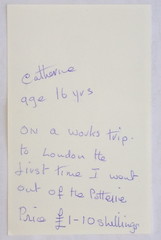

The article in The Sentinel shows a lovely photograph of my mum taken on a work trip to London. She was sixteen years old at the time and the photograph is of her standing by one of the fountains in Trafalgar Square. Written on the back it says, " Catherine aged 16 years on a trip to London the first time I had left The Potteries. Price £1.10s".

Joan can also remember this trip. She said they went by train and that the owner, John Aynsley came with them. She recalls he was very good looking, with blond hair and was lots of fun. She can remember him entertaining everyone by impersonating Al Jolson!

Joan said Aynsleys were good to work for. There was always a Christmas party that finished at 9.00pm and you could buy a ticket to win a kiss from the boss! She also told me about Dinner Dances but I doubt Mum would have attended these as she was too young.

These few years at Aynsleys certainly made an impression on mum, not least her appreciation of fine bone china and her ability to spot good quality pieces. In common with everyone else of her generation who came from The Potteries she always turned her cup over to see where it was made, a habit I've acquired too!

I don't know when she decided to leave but I do know she was always very ambitious and wanted to leave home to make a better life for herself. Beth recalls mum must have been eighteen when she left Longton to take up her nurses training in Stafford. In those days you couldn't leave home without parental consent before your were eighteen.

She got to know about the opportunity through a friend and I think needed a reference which she managed to get from the local Priest. I'm not exactly sure when she left but she was eighteen in November 1953.

Mum used to tell us about her training days at the Staffordshire General Infirmary on the Stone Road and how much fun and hard work it was.

She lived in the nurses accommodation and used to enjoy going to the Nurses Dances that were always a popular local event! It was at one of these dances that she met Dad who was a young draftsman at English Electric.

She qualified as a State Enrolled Nurse in 1958 and I understand she had to retake a year because her written work was not up to scratch. One of the signatures on her certificate is by the Matron who trained her, Matron Da Prato. I remember mum telling me about Matron Da Prato, she a very strict and a woman all the nurses feared, and no doubt most of the doctors too!

In 1958 mum and dad were married and the following year I was born. As was the convention then mum left work and became a full time wife and mother. With dad, they created a very happy home for their three daughters. Mum was a determined and resourceful woman who achieved her ambition to make a better life for herself.