In the original story, Pat Callaghan gave a good overview of the efforts which have been made to 'green' Stoke-on-Trent after its long history of industrial pollution and desolation due to the pottery, mining and steel industries.

This story has been created to give more detail about specific aspects.

(1966 – 76) My family and I came to village of Madeley, west of SoT, in 1966, almost half a century ago! I was a freelance broadcaster with the BBC – Radio 4, World Service, and Radio Stoke. It was just after the Clean Air Acts (date? ). Hundreds of bottle ovens from the Pottery industry had been polluting the area with black soot. Pottery, steel and coal mining industries declined, in 1968: SoT had more derelict land (2000 acres) than any other town in Britain. A huge reclamation project began to restore and green the landscape. FILM: (Ray Johnson). Reclamation sites, Joe Monks-Neil? Put the ‘Ills into the ‘Oles FILM: The last bottle oven firing in Stoke –on-Trent.

Main text to follow.

This is one of the best-known photos of a 'marl hole' in Stoke-on-Trent. It was only a couple of hundred yards from the centre of Longton, the southernmost of the SIX towns which federated in 1910 to form the county borough of Stoke-on-Trent. It was subsequently awarded city status in 1925.

The pottery in the background is taking clay from this ever-growing hole. Potteries always produced some reject ware and the white areas near top-centre and millions of such unsaleable ware being 'recycled' back in to the marl hole.

Given Stoke-on-Trent's long history of mining and pottery manufacture, if anyone is thinking of buying a house it's vital that they take proper steps to discover what might be underneath !

This is another aerial view of Longton in 1954 covering a similar area to the other image.

The Gladstone China factory - now the world-famous Gladstone Pottery Museum is at approximately 11 o'clock.

Even though smoke-control legislation had only just come into force - with a 10-year transition period - many factories were changing from the inefficient bottle-ovens for firing to more convenient gas and electric kilns. Only a few ovens are firing in this picture - at approximately 10 o'clock and some have already been demolished.

This photo shows how much smoke a single bottle-oven could produce.

The oven in question is either at Salisbury China or Beswicks and it perhaps about 150 yards from the market hall in the very centre of Longton.

For the inhabitants of the six towns life could be a very smoky experience during the 'good old days' when around 2000 bottle ovens were in use.

Each oven would have been fired about once a week using 10 - 15 tonnes of coal : add other coal used in industry and also that from domestic fires and the resulting air-pollution was probably the worst in the country at the time.

This marl hole is just off the former main Stoke - Fenton road and is still in use as a source of clay for brick production.

The horizontal distance of the whole picture is approximately 300 metres.

The bricks are not manufactured here : the clay is transported by road a few miles to the factory.

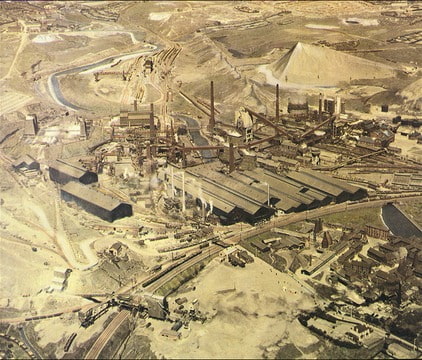

An aerial view of the former Stelton Bar steelworks at Etruria around 1950 - formerly the biggest single area of devastation in the whole city of Stoke-on-Trent.

Etruria : the largest area of desolation in Stoke-on-Trent

When Josiah Wedgwood opened his new factory at Etruria in 1769 the area was still basically countryside.

As one of the instigators of the Trent & Mersey canal, a major shareholder and unpaid treasurer of the project, Josiah was able to 'arrange' that the new canal ran right along the frontage of the new fact

This view of the Etruria valley prior to 1840 clearly shows Wedgwood's factory, as well as the house he built for himself nearby.

It's still very much a rural area.

This watercolour by local artist Anthony Forster shows the Grand Trunk canal (now known as the Trent & Mersey) running right next to the Etruria factory.

Please note that the canal water level is slightly below the ground-floor level of the factory.

This photo taken in the 1970s by Ken Cubley clearly shows how much mining subsidence had affected the former factory.

By the 1930s the factory ground floor was close to nine feet below canal level. Not only were the factory cellars flooding on a regular basis but this sometimes also affected the ground-floor. Repairs to the factory bottle-ovens to fix subsidence damage were becoming ever more frequent and expensive.

Apart from this, pollution from the Shelton Bar steelworks which had grown over the last century was causing an ever-increasing amount of reject ware being produced.

As a result of this the factory decided to look for a new 'home in the countryside' - as the original site had been - and the company moved completely to its new site in Barlaston about six miles away.

This photo from Staffordshire Past Track is dated 1937 and shows an area of Berry Hill which is 'lucky' enough to have both a marl hole and a mine spoil heap.

More information :- http://www.search.staffspasttrack.org.uk/engine/resource/default.asp?resource=11787

The problem of how to deal with mine waste heaps is not one which has only been raised and discussed recently - there was a debate in Parliament on the issue in 1936 - http://www.theyworkforyou.com/debates/?id=1936-05-14a.679.5

Possibly the greatest driver for dealing with the issue was the Aberfan disaster in October 1966, when slippage of a mine spoil heap caused the death of 116 schoolchildren and 28 adults.

This aerial photo shows the regenerated Garden Festival site around 7 months before the opening date.

Compare this with the earlier photo of the Shelton Bar steelworks !

In the 1980s major efforts were made to clean up the marl holes, mine waste heap and - particularly - the large area formerly occupied by the Shelton Bar steelworks.

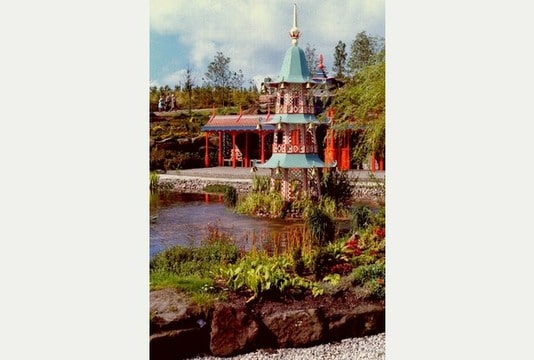

Waste heaps were grassed over, marl holes filled and the Shelton Bar site became the Stoke-on-Trent Garden Festival site in 1986.

The city won a number of awards for its regeneration efforts.

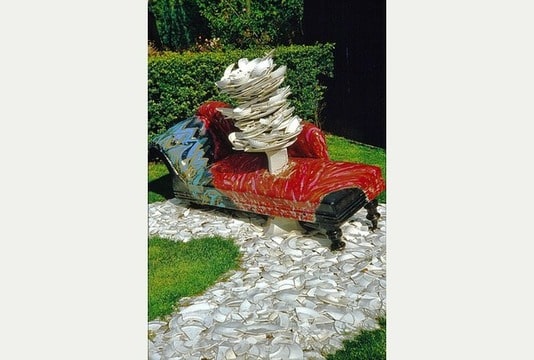

Permission to use this photo of the Twyford toilet fountain has been kindly given by Terry Woolliscroft.

As a reminder of Stoke's pottery industry, this was a sculpture made from 'shraff' - damaged / reject ceramics. This is exactly the sort of material which, in former times, would have been used to fill the 'oles.

The garden festival also had a room with its ceiling and walls covered with bone china plates.

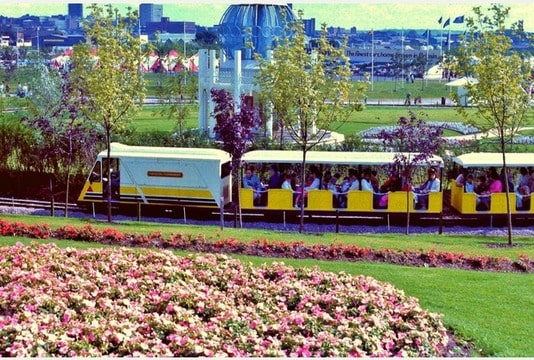

This fine flower display is complemented by the steelworks rail-car as a reminder of what used to stand on the site.

The festival train helped people get from place to place within the large garden festival site.

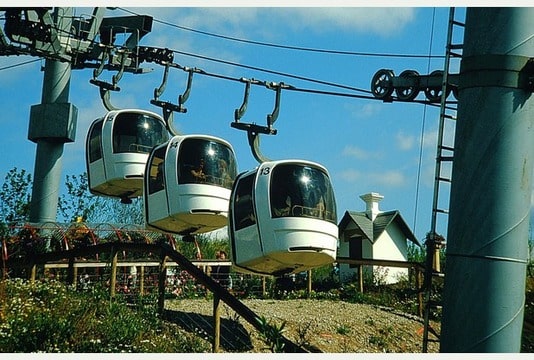

The cable-car system linked parts of the site but was also designed to help people with reduced mobility reach some of the sights which had steep approaches on foot.